In 1914 Germany controlled the Chinese port of Tsingtao, now Qingdao, on a similar basis to British control of Hong Kong. Vice Admiral Maximilian von Spee’s East Asia Squadron of two armoured and three light cruisers was based at Tsingtao, but none of its ships were there when war began between Britain and Germany.

The light cruiser SMS Emden had been in Tsingtao, but sailed on 31 July. Another light cruiser, SMS Leipzig, was on the west coast of Mexico, protecting German interests during the Mexican Revolution. The third, SMS Nürnberg, was on her way to relieve Leipzig. The two armoured cruisers, Spee’s flagship SMS Scharnhorst and SMS Gneisenau, were on a cruise through German Pacific islands.

At Hong Kong the Royal Navy had the armoured cruisers HMS Minotaur, which was slightly superior to either of Spee’s armoured cruisers, and HMS Hampshire, which was inferior to Spee’s ships, two light cruisers, eight destroyers and three submarines. The pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Triumph had been in reserve at the start of the war, but was quickly recommissioned. There were insufficient sailors available to fully crew her, but two officers, six signallers and 100 other men of the Duke of Cornwall Light Infantry volunteered for sea service. This gave the British a narrow margin over Spee in Chinese waters.

Further south, the battlecruiser HMAS Australia gave the British Empire naval forces a big superiority In Australasian waters. There were also a number of old French ships in Asia.

However, the major question for Spee was whether or not Japan would enter the war. It issued an ultimatum to Germany on 15 August demanding that Germany withdraw its ships from Chinese and Japanese waters and hand Tsingtao over to Japan. It declared war eight days later. A naval blockade of Tsingtao by a largely Japanese force that included a small British contingent began on 27 August. A land siege began on 31 October; the heavily outnumbered defenders surrendered on 7 November.

This meant that the German pre-war plan for Spee’s squadron to conduct commerce warfare, supplied from Tsingtao, was no longer feasible. By 12 August he had gathered Emden, Nürnberg, the two armoured cruisers and a number of supply ships at Pagan in the Marianas. The strength of the enemy and his lack of bases and coal supplies meant that his squadron could not operate in Indian, East Asian or Australasian waters. The high coal consumption of his armoured cruisers was a particular problem.

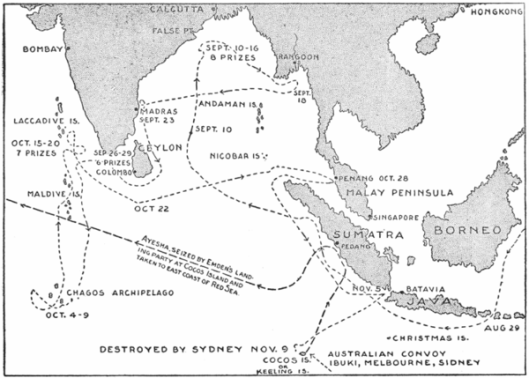

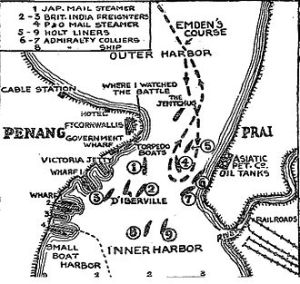

Spee did, however, detach Emden and the supply ship Markomannia, to operate in the Indian Ocean. One fast ship could raid commerce and obtain its coal supplies from prizes. The highly successful cruise of Fregattenkapitän Karl von Müller’s Emden will be the subject of a later post.

Spee also sent two armed merchantmen, Prinz Eitel Friedrich and Cormoran, south to raid commerce. The former captured and sank 11 merchantmen with a total displacement of 33,423 tons before coal supply problems forced her to accept internment at Newport News on 11 March 1915.[1]

Cormoran entered the US territory of Guam on 14 December 1914 with her coal bunkers almost empty. She was not allowed to re-coal, so could not leave, and was scuttled on 7 April 1917 after the USA declared war on Germany.

Spee’s squadron moved slowly in order to conserve coal, avoiding contact with Allied forces. He sent Nürnberg to Honolulu on 22 August in order coal and to send and pick up mail and to send orders to German agents in South America to obtain coal and other supplies for the squadron.

The capture and destruction of German wireless stations in the Pacific by Australian and New Zealand forces made it hard for Spee to communicate with Germany and its agents. He also wanted to maintain radio silence as much as possible.

On 12 October Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and Nürnberg were at Easter Island, a remote Chilean possession where they could coal in security. The light cruiser SMS Dresden, which had been stationed in the Caribbean before the war, was already there. Two days later they were joined by Leipzig; her appearance off San Francisco on 11 August and erroneous rumours that she was accompanied by Nürnberg ‘paralysed the movements of [British] shipping from Vancouver to Panama.’[2] However, she was forced to lie low after the Japanese entered the war, since the armoured cruiser IMS Idzumo had been off Mexico, protecting Japanese interests.

On 3 September Rear Admiral Sir Christopher Cradock, until then commanding the 4th Cruiser Squadron in the West Indies, had been appointed to command the South American Station. He had his flagship the armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope, the County or Monmouth class armoured cruisers HMS Monmouth and Cornwall, the Town class light cruisers HMS Bristol and Glasgow and the armed merchant cruisers HMS Carmania, Macedonia and Otranto. He lost Carmania on 14 September because of damage that she sustained when sinking the German commerce raider SMS Cap Trafalgar.

The armoured cruiser HMS Defence, then in the Mediterranean, was ordered to head to Gibraltar on 10 September and then to South America after engine room defects had been corrected. A telegram of 14 September told Cradock that Defence was joining him, although she had not set off, and that the pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Canopus was on her way. Spee’s two armoured cruisers were likely to appear at the Magellan Straits. He was told that:

‘Until Defence joins keep at least Canopus and one County class with your flagship. As soon as you have superior force search the Magellan Straits with squadron, being ready to return and cover the River Plate, or, according to information, search north as far as Valparaiso, break up the German trade and destroy the German cruisers.’[3]

However, two days later he was told the German armoured cruisers had been seen at Samoa on 14 September and had left heading north west. He was now told that ‘[c]ruisers need not now be concentrated’ and ‘the German trade on the west coast of America was to be attacked at once.’[4]

On 14 October the Admiralty informed Cradock that it had accepted his proposal that he should concentrate Good Hope, Monmouth, Canopus, Glasgow and Otranto and that a second cruiser squadron should be formed on the east coast of South America. It would be commanded by Rear Admiral Archibald Stoddart and would consist of his flagship the County class armoured cruiser HMS Carnarvon, her sister HMS Cornwall, the light cruiser HMS Bristol and the armed merchant cruisers HMS Macedonia and Orama. HMS Defence would join Stoddart’s squadron when she arrived.

According to the Naval Staff Monograph on Coronel, a detailed report prepared by RN staff officers after the war for internal use only:

It was apparently intended that [Cradock’s] squadron, with the exception of the Glasgow, should concentrate and presumably remain at the Falkland Islands, but the actual instructions sent on October 14th did not emphasise this and certainly did not debar him from going to the west.[5]

The British Official History argues that the formation of a new squadron on the east coast and a mention of combined operations made Cradock assume that his orders of 5 October were still in effect, so he should ‘concentrate all his squadron on the west coast “to search and protect trade” in co-operation with his colleague.’[6] HMS Kent, another County class cruiser, was sent to join Cradock, but he does not seem to have been informed of this, and she was diverted elsewhere, so never joined his command.

The Admiralty had made a ‘fairly accurate’ estimate of Spee’s movements.[7] Cradock left the Falkland Islands in Good Hope on 22 October to rendezvous with Monmouth, Glasgow and Otranto at a secret coaling base in south west America. He left Canopus to convoy colliers because he believed that her speed was only 12 knots. However, she was actually capable of 16.5 knots, but her ‘Engineer Commander…was ill mentally…and made false reports on the state of the machinery.’[8]

On 26 October Cradock ordered Defence to join him, but the Admiralty countermanded this the next day, ordering her to join Stoddart. Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, claimed that this telegram did not reach Stoddart and a note for the Cabinet said that it is ‘not certain that this message reached Good Hope.’ However, Paymaster Lloyd Hirst of Glasgow, whose ship did receive it, wrote that it is ‘practically certain’ that it reached Cradock just before the battle.[9]

Glasgow went to the port of Coronel in south west Chile to send and receive messages on 31 October. By the time that they reached the Admiralty Lord Fisher had been re-appointed First Sea Lord following the resignation of Prince Louis of Battenberg on 29 October because of ‘rising agitation in the Press against every one German or of German descent.’[10] Fisher ordered Defence to join Cradock and sent a signal making it ‘clear that he was not to act without the Canopus.’[11] It never reached Cradock.

Cradock’s ships had picked up radio traffic from Leipzig, so were searching for her. Spee had used only her wireless in order to hide the presence of his other ships.[12] Spee was aware that Glasgow had been in Coronel, so was searching for her.

At 4:20 pm on 1 November the British ships were in a line 15 miles apart when Glasgow sighted smoke.[13] Shortly afterwards she could see two four funnelled cruisers [i.e. and a three funnelled cruiser. They were Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and a light cruiser. She informed Cradock, whose ship was then of sight, by wireless.

Good Hope came into view at 5:00 pm, and at 5:47 pm Cradock formed his ships into line of battle and closed the range.

Spee acted more cautiously, later writing that he ‘had manoeuvred so that the sun in the west would not disturb me.’[14] Captain John Luce of Glasgow commented that:

‘The sun was now setting immediately behind us, as viewed from the enemy, and as long as it remained above the horizon, all the advantage was with use, but the range was too great to be effective.

…

Shortly before 7:00 pm, the sun set, entirely changing the conditions of visibility, and whereas in the failing light it was difficult for us to see the enemy, our ships became clearly silhouetted against the afterglow, as viewed from them’[15]

Even without this tactical advantage, the odds in the battle hugely favoured the Germans. Their crews had served on their ships for years and were well trained. Many German sailors were conscripts, but Spee’s men were all long service volunteers because of the time that their ships spent away from Germany. The crews of both British armoured cruisers had been assigned to their ships at the outbreak of war and neither ship had had much opportunity for gunnery practice.

Many histories of the war at sea state that Good Hope and Monmouth both had crews largely consisting of reservists.[16] However, the Naval Staff Monograph makes no mention of Monmouth’s crew being mostly reservists, whilst stating that HMS Good Hope:

‘which was the only [British] ship carrying heavy guns, was a third fleet ship which had been commissioned for mobilisation, then paid off and commissioned with a fresh crew consisting largely of Royal Naval Reserve men, coastguards, and men of the Royal Fleet Reserve.’[17]

On 23 December 1915 Commander Carlyon Bellairs MP in the House of Commons asked the First Lord of the Admiralty, Arthur J. Balfour, if it was true that both ships had crews largely made up of reservists and whether or not their guns were fit for action. Balfour replied that:

These vessels were not commissioned entirely with reserve ratings. Each of them had on board not less than the authorised proportion of active service ratings; and, in fact, His Majesty’s ship Monmouth had a crew composed almost entirely of active service men. No guns in these ships had been retubed: they were all serviceable.[18]

It appears that a fact about Good Hope‘s crew has at some point been exaggerated to refer to both ships and has then been repeated.

The following table shows that Cradock’s squadron was clearly outgunned. The final column omits some guns on the two British armoured cruisers that could not be used in bad weather and two ships that took little part in the battle. Otranto was not intended to fight warships and Nürnberg was some distance from the rest of the German squadron. She arrived after the battle was decided, though in time to finish off the crippled Monmouth.

| Ship |

Completed |

Tonnage |

Speed (knots) |

Guns |

Weight of Broadside (lbs) |

Broadside Usable at Coronel (lbs) |

| Scharnhorst |

1907 |

11,420 |

23.8 |

8 x 8.2″ |

1,957 |

1,957 |

| 6 x 5.9″ |

| Gneisenau |

1907 |

11,420 |

23.8 |

8 x 8.2″ |

1,957 |

1,957 |

| 6 x 5.9″ |

| Nürnberg |

1908 |

3,400 |

23.0 |

10 x 4.1″ |

176 |

– |

| Leipzig |

1906 |

3,200 |

23.3 |

10 x 4.1″ |

176 |

176 |

| Dresden |

1909 |

3,592 |

24.5 |

10 X 4.1″ |

176 |

176 |

| German Total |

|

|

|

|

4,442 |

4,266 |

| Good Hope |

1902 |

14,100 |

23.0 |

2 x 9.2″ |

1,560 |

1,160 |

| 16 x 6″ |

| Monmouth |

1903 |

9,800 |

22.4 |

14 x 6″ |

900 |

600 |

| Glasgow |

1911 |

4,800 |

25.3 |

2 x 6″ |

325 |

325 |

| 10 x 4″ |

| Otranto |

|

|

17.0 |

4 x 4.7″ |

90 |

– |

| British Total |

|

|

|

|

2,875 |

2,085 |

| Source: Marder, A. J., From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow; the Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904-1919. 5 vols. (London: Oxford University Press, 1961-70), vol. ii, p. 109. |

Spee noted in his after action report that the heavy seas made things very difficult for the gunners:

‘With the head wind and sea, the ships laboured heavily, particularly the light cruisers on both sides. Spotting and range-finding suffered greatly from the seas, which came over the forecastle and conning tower, and the heavy swell obscured the target from the 15-prs on the middle decks, so that they never saw stern of their adversary at all, and the bow only now and then. On the other hand , the guns of the large cruisers could all be used, and shot well.’[19]

The high seas were bad for both sides, but even worse for the British, as the design of their two armoured cruisers meant that they could not fire their main deck 6 inch guns in heavy seas. The German guns that had difficulty firing were smaller ones, not listed in the table above.

The Germans opened fire at about 7:05 pm at a range of 12,000 yards. Scharnhorst fired at Good Hope and Gneisenau at Monmouth. Leipzig and Dresden both fired at Glasgow, since Otranto had moved out of range. Luce ordered his guns to fire independently as the roll of his ships slowed the rate of firing and firing salvos would have slowed it even further, but the Germans used salvo firing.

The Germans quickly found the range. The third salvo hit Good Hope, apparently putting her forward 9.2 inch gun out of action and starting a fire. Monmouth was soon also on fire. At some point, she headed off to starboard and became separated from Good Hope. Glasgow could not then follow Good Hope, as she would then have masked Monmouth’s fire. At least one of the British armoured cruisers was on fire at any one time.

Around 7:45 pm Good Hope lost way. About five minutes later she suffered ‘an immense explosion…the flames reached a height of at least 200 feet and all who saw it on board [Glasgow] had not doubt she could not recover from this shock.’[20] Good Hope then ceased fire.

Monmouth turned away to starboard, followed by Glasgow. It was now dark, and they were soon out of sight of the enemy. However, Monmouth was continuing to turn to starboard, steering north east and taking her closer to the Germans. Luce received no reply to a signal at 8:20 pm. The moon had now risen above the clouds, and Glasgow could see the Germans., although Luce thought that they could not see her.

Luce could not see how he could help the stricken Monmouth, and said that ‘with the utmost reluctance to leaving her, I felt obliged to do so.’[21] Glasgow headed west north west at full speed, which put the Germans astern of her, and was out of sight of them by 8:50 pm. She saw firing about 12 miles away 30 minutes later.

Luce’s intention was to find Canopus and warn her of what had happened. Otranto also escaped. The action had taken place beyond the range of her guns, and she was a large ship, whose presence in the British line would have done nothing except help the Germans to find their range. After zigzagging for a period, she withdrew.

The firing that Glasgow had seen came from Nürnberg and was directed at the helpless Monmouth. The German ship stopped firing for a period in order to give the British ship a chance to surrender, but she did not do so, giving the Germans, in the words of the British Official History, ‘no choice…but to give her the only end that she would accept.’[22] The heavy seas made it impossible for the Germans to rescue any survivors.

The Germans had sunk two British armoured cruisers with the loss of all their 1,570 men. Glasgow was hit five times, but only four of crew were wounded, all slightly. Only three Germans were wounded. Naval History.net lists all the British dead. It can be seem that few of Monmouth’s crew were reservists of the Royal Fleet Reserve (RFR), Royal Naval Reserve (RNR) or Coast Guard. A significant proportion of Good Hope’s crew were reservists, but not the 90% sometimes claimed.

The unanswered questions are: what would have happened if Cradock’s force had included either HMS Defence or Canopus?; and why did he seek out the enemy when his squadron was so clearly out classed?

Defence was the last British armoured cruiser built, so was newer and more powerful than Spee’s two armoured cruisers: 14,600 tons, speed of 23 knots and armed with four 9.2 inch and ten 7.5 inch guns. The British would then have had an advantage in firepower, but not by so overwhelming a margin as to guarantee victory if the German gunnery or tactics were better.

Canopus, as was often the case for a battleship of her day was no bigger than an armoured cruiser, but had larger guns: 12,950 tons, designed for 18 knots but only capable of 16.5 in 1914 and armed with four 12 inch and twelve 6 inch guns. Her 12 inch guns had a range of 14,000 yards, only 500 more than the 8.2 inch guns of Spee’s armoured cruisers.[23] Again, the Germans might still have won despite her presence.

Another possibility is that Spee might not have accepted battle with a force including a battleship. He wrote after the battle that he believed that the British:

‘have her another ship like Monmouth; also it seems, a battleship of the Queen type, with 12-inch guns. Against the last-named we can hardly do anything; if they had kept their forces together we should, I suppose, have got the worst of it.’[24]

The Queen class were larger (15,000 tons) than Canopus, but had a similar armament.

There are three theories about Cradock’s decision to seek battle. One, propounded by Luce is that he ‘was constitutionally incapable of refusing or even postponing action, if there was the slightest chance of success.’[25] Rear Admiral Sir Robert Arbuthnot said when he heard the news of Coronel that Cradock ‘always hoped he would be killed in battle or break his neck in the hunting field.’[26]

Another, put forward by Glasgow’s navigator Lieutenant Commander P. B. Portman, is that the Admiralty:

‘as good as told him that he was skulking at Stanley…If we hadn’t attacked that night, we might never have seen [Spee] again, and then the Admiralty would have blamed him for not fighting.’[27]

Cradock is known to have written to another admiral that ‘I will take care I do not suffer the fate of poor Troubridge’, who was then facing court martial for not having attacked SMS Goeben.[28]

The final, and most common, theory is that Cradock realised that realised that his squadron had no chance against Spee’s, but thought that that by damaging the Germans and force them to use up ammunition a long way from any base he could ensure that they would be beaten in the next action. If so, he partly succeeded: the Germans suffered little damage, but Scharnhorst used 422 8.2 inch shells and Gneisenau 244 out of a total of 728 carried on each ship.[29]

Subscribers to this theory include Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon, Balfour in his eulogy when unveiling Cradock’s memorial at York Minster, Sir Julian Corbett who quotes Balfour’s eulogy in the Official History of the RN in WWI, Churchill, Hirst and David Lloyd George.[30] It was also put forward in a film called The Battles of Coronel and the Falkland Islands made in 1927 that has been recently restored and re-released.

Whatever Cradock’s motivation, the blame for the defeat should rest with the Admiralty. It knew the strength of Spee’s squadron and that it was heading for South America. However, it ignored the military principle of concentration, establishing two weak squadrons in the area instead of combining Cradock and Stoddart’s forces into a single squadron capable of defeating Spee.

Spee had won a victory, but he knew that the British would seek revenge. At a dinner held in his honour by the German residents of Valparaiso he refused to drink a toast to the ‘[d]amnation of the British Navy’, instead saying that ‘I drink to the memory of a gallant and honourable foe.’ On being offered a bouquet of flowers, he said that ‘[t]hey will do nicely for my grave.’[31]

[1] P. G. Halpern, A Naval History of World War I (London: UCL Press, 1994), p. 82.

[2] C. E. Fayle, Seaborne Trade., 3 vols. (London: HMSO, 1920). vol. i, p. 165.

[3] Naval Staff Monograph (Historical) vol. i. ‘1. Coronel’, p. 19

[4] Ibid., p. 20.

[5] Ibid., p. 28.

[6] J. S. Corbett, H. Newbolt, Naval Operations, 5 vols. (London: HMSO, 1938). vol. i, p. 318.

[7] Ibid. vol. i, p. 319.

[8] A. J. Marder, From the Dreadnought to Scapa Flow; the Royal Navy in the Fisher Era, 1904-1919, 5 vols. (London: Oxford University Press, 1961-70). vol. ii, note 8, p. 107.

[9] Ibid. vol. ii, p. 108.

[10] Corbett, Newbolt, Naval. vol. i, p. 246.

[11] Ibid. vol. i, p. 344.

[12] Halpern, Naval, p. 93.

[13] Times and ranges are from NA, ADM 137/1022, ‘Coronel Action, 1 November 1914’. ‘HMS Glasgow – Reports of Coronel Action, 1/11/14’, Captain John Luce, pp. 15-27.

[14] Quoted in Corbett, Newbolt, Naval. vol. i, p. 349.

[15] ADM 137/1022, pp. 20-21.

[16] G. Bennett, Naval Battles of the First World War (London: Pan, 1983), pp. 71-72; G. A. H. Gordon, The Rules of the Game: Jutland and British Naval Command (London: John Murray, 1996), p. 291; Halpern, Naval, p. 92; R. A. Hough, The Great War at Sea, 1914-1918 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), p. 90; R. K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (London: Jonathan Cape, 2004), pp. 203-4. pp. 203-4. Massie gives his source as being a book by an officer of HMS Glasgow, Lloyd Hirst, Coronel and After (London: Peter Davies, 1934), p. 15

[17] Naval Staff vol. i.

[18] <<http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/written_answers/1915/dec/23/loss-of-hms-good-hope-and-monmouth>> Accessed 30 October 2014.

[19] ADM 137/1022. Naval Engarment off Coronel on 1st November 1914′, September 1915: Graf von Spee’s despatch, Weser Zeitung, 2 July 1915, p. 361.

[20] Ibid. ‘HMS Glasgow – Report of Coronel Action, 1/1/14’, Captain John Luce, p. 20.

[21] Ibid., p. 21.

[22] Corbett, Newbolt, Naval. vol. i, p. 354.

[23] Marder, From. vol. ii, p. 106.

[24] ADM 137/1022. ‘Naval Engagement off Coronel on 1st November 1914’ September 1915: Letter of 2 November 1914, Kieler Neuste Nachrichten, 20 April 1915, p. 358.

[25] Quoted in Marder, From. vol. ii, p. 110.

[26] Quoted in Ibid. vol. ii, p. 115.

[27] ADM 137/1022. ‘Letter to Miss Ella Margaret Mary Haggard, 10 November 1914’, p. 369

[28] Quoted in Marder, From. vol. ii, p. 111.

[29] Ibid. vol. ii, p. 118.

[30] Corbett, Newbolt, Naval. vol. i, pp. 356-57; Marder, From. vol. ii, p. 111.

[31] Quotations in this paragraph are from Massie, Castles, p. 237.