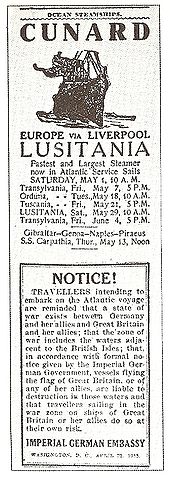

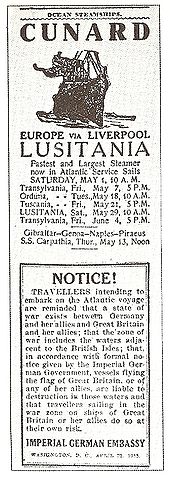

On 1 May 1915 the Cunard Liner RMS Lusitania, captained by Captain William Turner, left New York for Liverpool. The German Embassy to the USA took out advertisements in US newspapers warning passengers that the waters round the British Isles were a war zone in which merchant ships were liable to be sunk without warning. The German ad did not specifically mention the Lusitania or Cunard, but the most commonly reproduced version shows it to be placed below Cunard’s announcement of the departure times of its services to Liverpool.[1]

The day before the Lusitania sailed, the German U-boat U-20 departed from Germany. Her captain, Kapitänleutnant Walther Schweiger, had orders to attack transports off Liverpool.[2] He had been in command when U20 sank three British merchants hips off Le Havre on 30 January, before the German declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare. He had also unsuccessfully tried the sink the hospital ship Asturias, claiming that he thought that she was a troopship and could not in any case have been carrying wounded as she was heading from the United Kingdom.[3]

Schweiger sank the schooner Earl of Lathom (132 tons), carrying bacon, eggs and potatoes to Liverpool, by gunfire on 5 May off the Old Head of Kinsale on the south coast of Ireland after giving her crew time to abandon ship. Later that day he fired a torpedo at a 3,000 ton steamer but missed.

The next day he made a surface attack on the steamer Candidate (6,000 tons) in the St George’s Channel. She was heading for Jamaica with a cargo of hardware and groceries. She tried to flee into fog banks, but was eventually forced to stop by gunfire. Schweiger fired a torpedo at her after the crew had abandoned ship, but she would not sink, so U20 had to finish her off by gunfire.

Later that day, after being unable to get into position to torpedo the 16,000 ton passenger liner Arabic, Schweiger fired a torpedo at the steamer Centurion (6,000 tons), en route to Durban. She did not sink, and he finished her off with another torpedo after the crew had abandoned ship. This left him with only three torpedoes; his standing orders said that he was to keep a minimum of two for the return journey.[4]

The large number of patrol ships in the area meant that U-20 would have to proceed to Liverpool submerged, which would be difficult because fog restricted visibility using the submarine’s periscope. Consequently, Schweiger decided to remain in the entrance to the Bristol Channel.

On 7 May he spotted the cruiser HMS Juno, which he followed in the hope of an opportunity to torpedo her. However, she headed for the Queenstown (now Cobh) on the south coast of Ireland. Schweiger, not wanting to approach a well defended naval base, turned away to the west.

Soon afterwards Schweiger spotted a four funnelled liner off the Old Head of Kinsale. It did not appear that he could get his boat into an attacking position until the liner, which was the Lusitania, turned towards U20. Schweiger fired a torpedo at 2:10 pm at a range of 700 metres. It struck just astern of the bridge, producing a large explosion and causing the ship to stop and list.

Schweiger, realising that the Lusitania was doomed, left the scene. He fired a torpedo that suffered a mechanical failure at another Cunarder later the same day.

An SOS signal from the Lusitania was received at 2:11 pm. HMS Juno was ordered to go to her aid, in contravention of Admiralty orders that the old ships of Cruiser Force E at Queenstown should not be put at risk of submarine attack. All available tugs, small craft and patrol vessels were also sent. At 2:33 pm a signal reporting that the Lusitania had sunk was received. Juno was then recalled.[5]

The Lusitania was capable of only 21 knots rather than her full speed of 24 knots. This was because of a commercial decision by Cunard to use only 18 of her 24 boilers in order to make it economic to run her when passenger traffic was reduced in wartime: she was capable of carrying 2,350 passengers and had a crew of 750 in peacetime.[6] Because of the fog Turner had reduced her speed to 15 knots, but had increased it to 18 knots by the time of the sinking as visibility had improved.[7]

U20 returned to Wilhemshaven on 13 May with ‘only 19 tons of oil left’, according to the British Naval Staff Monograph, written in 1925 for internal Royal Navy use only.[8] This phrase makes it sound as if his tanks were almost dry, but U20’s fuel capacity was only 77 tons:[9] presumably 1925 RN officers would have been expected have at least a rough idea of this number.

A total of 1,201 people were killed when the Lusitania sank: 785 out of 1,257 passengers, including 128 Americans, 413 of the 702 strong crew and three stowaways. Some sources quote 1,198, omitting the stowaways. [10] They were German speakers, so were suspected of being spies or saboteurs and held in confinement below decks.[11] Only six out of 48 lifeboats reached Queenstown intact.[12]

Many of the survivors were rescued by small craft from Queenstown, including the Indian Prince and the Flying Fox, and by fishing vessels such as the Peel 12 and the Bluebell.[13]

The Lusitania’s cargo included a number of cases of munitions: 4,200 each containing about 1,000 rifle cartridges, 1,250 of 3.3 inch shrapnel shells and 18 of percussion fuses. The shells and fuses were stated in the official manifest to be without explosives. it was also carrying material for military uniforms and leather equipment.[14]

These items were all classed as contraband under the rules of cruiser warfare. These rules entitled Schweiger to stop and search Lusitania and, on finding the contraband, to require the crew and passengers to take to the lifeboats before he sank the liner and her cargo. They did not allow him to sink her without warning. However, he would have been putting his boat at severe risk by acting in accordance with the rules so close to the British base at Queenstown.

Some media sources, including The Guardian and The Daily Telegraph, have suggested that the British government admitted only recently that the Lusitania was carrying munitions after some Foreign Office documents from 1982 were made public. They dealt with concerns that salvage operations then proposed might reveal the presence of explosives. However, the fact that she was carrying munitions was revealed by the 1918 Mayer hearing into lawsuits against Cunard, although allegations that there were more explosives on board than then admitted persist.[15]

There are several mysteries about the sinking of the Lusitania. One is when Schweiger realised which ship he had sunk. The Naval Staff Monograph, sourcing the German Official Naval History, says that it was not until he saw her name painted on her bows in gold letters, but notes that Lusitania’s captain says that this had been painted over.[16]

German U-boats carried a pilot, a merchant navy officer intended to help with ship identification. Simpson says that U20’s pilot identified the liner as being either the Lusitania or her sister the Mauretania before firing.[17]

Preston argues that there were only five four funnelled British liners and that the Germans knew that the Lusitania was the only one of them that could be inbound on 7 May. She contends that Schweiger’s war diary was later altered to conceal the fact that he knew exactly what ship he was torpedoing.[18]

A major issue is that there were two explosions. The British Official History of The Merchant Navy claims that Schweiger fired two torpedoes, whilst quoting a German source that says that he did not.[19] It is now accepted that he fired only one.

Colin Simpson argues that Schweiger’s torpedo flooded the starboard coal bunkers and cased a 15 degree list, but that it was the second explosion that sank the Lusitania, which he believes was caused by the explosion of contraband. He argues that this is supported by the fact that relevant Admiralty papers, including those of Captain Reginald Hall, Director of Naval Intelligence, and Captain Guy Gaunt, Naval Attaché in Washington, were unavailable when he researched his 1972 book.[20] Some of Hall’s papers are now available at Churchill College, Cambridge, but they do not appear to include any from May 1915.

Diana Preston goes through a number of theories to explain the second explosion:[21]

- The munitions that were known to be carried. The shells would have remained inert even if they, contrary to the manifest, contained their powder and propellant charges because they would still have lacked their fuses, a standard procedure during transport. The rifle cartridges would not have exploded, as shown by an example in 1972 when a railway wagon full of United States Navy bullets caught fire but did not explode.

- Detonation of less stable explosives that it has been rumoured but never proven were secretly on board. The Scientific American concluded soon after the sinking that such as explosion would have blown the Lusitania’s bows off. A survey of the wreck by the oceanographer and underwater archaeologist Robert Ballard showed no such damage.

- Aluminium powder that the manifest showed was being transported to the Woolwich Arsenal. This is highly volatile and can ignite spontaneously in air. However, it would also have created a much larger explosion and greater damage than actually occurred. Some of the crew from the cargo area survived, which they would not have done in this case.

- Coal dust explosion. This can ignite if exposed to a spark or flame in the right conditions. However, seepage of sea water into the hull, moist air from the boilers and sea water from the flooding that followed the torpedo hit mean that the conditions were not right.

- A boiler explosion. This is the only explanation that would have produced the steam reported by survivors. The sound would have been carried up through the funnels and vents, explaining why the explosion sounded loudest to those on deck. The main flaw is that some of the boiler room personnel survived, which would not have been the case if the boilers exploded immediately. However, a delay of a minute or two would have allowed a few men to get out.

- Failure of the steamlines that carried high-pressure superheated steam from the boilers to the turbines. The effect of this fits the reports of survivors.

Preston argues convincingly that ‘steamline explosions are easily the most likely source of the second explosion’, quoting Captain Turner as telling the Mayer hearing that ‘The torpedo burst the steampipe and put the engines out of commission.’[22]

However, Preston’s conclusion is that there were probably a number of explosions, and that the main cause of the sinking of the Lusitania was that she was not designed to survive a torpedo hit in a vital area.[23]

It may seem strange that Lusitania, a ship displacing more than 30,000 tons sank about 20 minutes after being hit by a single torpedo. However, three months later the Arabic went down nine minutes after being hit by a torpedo. HMS Aboukir, an armoured cruiser, albeit an elderly one with weak underwater protection, took only nine minutes to sink after being hit by a single torpedo.[24] The old Ottoman battleship Mesudiye also sank after being hit by only one torpedo from HMS B11.

The Germans subsequently claimed that the Lusitania was a Royal Navy auxiliary cruiser. Her construction and that of the Mauretania had been financed by a cheap loan from the British government, which was concerned that Cunard was struggling to compete with its German and US rivals. In return, they were to be built to the Admiralty’s specifications and were to be taken out of passenger service and converted into armed merchant cruisers if hostilities threatened. A set proportion of their crews must be members of the Royal Naval Reserve. In 1913 the Lusitania was refitted to allow her to carry 12 6 inch guns.[25]

However, the Lusitania was never actually fitted with guns. The Admiralty considered doing so at the start of the war, but decided that she was too expensive to fuel relative to her value as a warship. Inspections by US customs officials and film of her leaving New York on her last voyage showed no sign of any armament.[26] Most of the naval reservists on board the Lusitania in 1914 had by May 1915 been called up by the RN, leaving her with an inexperienced crew.[27]

The Germans also alleged that the Lusitania was carrying Canadian troops across the Atlantic. If they were travelling as an armed and organised unit, rather than as individuals, this would have made her a troopship liable to be sunk without warning. There is no evidence in archives or the accounts of survivors to support this claim. One of the dead passengers, Robert Matthews, was a Lieutenant in the 60th Rifles of Canada, a militia unit. However, he had not attended any drills in the winter of 1914-15, had been rejected for a commission in the Canadian Expeditionary Force and was travelling with his mistress.[28]

The other main conspiracy theory is that the British deliberately put the Lusitania in danger in the hope that she would be sunk, bringing the USA into the war on the Allied side. However, the British in 1915 were happy to have the USA as a friendly neutral munitions supplier rather than as an ally that would want to impose its views on a peace settlement.[29]

As with most conspiracy theories, there is no archival evidence to support it, but the proponents of conspiracy theories always argue that the absence of evidence is itself part of the conspiracy. There are some gaps in British government correspondence during the period in question, notably from Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty and Admiral Lord Fisher, the First Sea Lord.

However, the two were then mainly pre-occupied with their dispute over the Dardanelles, Churchill was in France at the time of the sinking and Fisher was close to a nervous breakdown. Their by then poor relations make it unlikely that they would have co-operated in a conspiracy or that either would have kept quiet if the other had been responsible for one. The other contender was Hall, but if he did conspire, it is more likely to have been by omission than commission by not passing on intelligence about U-boat movements.[30]

A conspiracy to have the Lusitania sunk left a lot of things to chance. U20 might not have been in the right place to meet her. The Lusitania might not have approached at an angle that gave Schweiger such a good chance. He might not have aimed so well. His torpedo might have suffered a technical failure, as did the one that he fired the next day. One torpedo might not have been enough, although an unsuccessful attempt to sink the Lusitania might have achieved the objective of the alleged conspirators without serious loss of life.

Like Preston, I have a preference for the cock up theory over the conspiracy one.[31] The Lusitania was not warned that U-boats were operating in the area because the Admiralty was then lax in issuing warnings. Initiative was discouraged and information shared even less widely than security dictated. The Lusitania did not have an escort because it was thought that her speed made her safe. The Admiralty’s anti-submarine strategy was then to patrol waters where there was a risk of U-boat attack rather than to escort merchant ships.

Even in the Second World War, when merchant ships normally sailed in escorted convoys, fast liners such as the Queen Elizabeth and Queen Mary carried large number of Canadian and Us troops across the Atlantic unescorted, depending on their high speed to avoid U-boat attack.

The sinking of the Lusitania caused great damage to US-German relations. President Woodrow Wilson wrote a note that stated that:

‘Manifestly, submarines cannot be used against merchantmen…without an inevitable violation of many sacred principles of justice and humanity.’[32]

This comment formed part of a note that was sent to Germany despite the protests of Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan that it was too pro-British. It arrived on 15 May, by when Kaiser Wilhelm had already ordered his U-boats to cease sinking neutral ships. The navy ignored this order, and Wilhelm reiterated it on 1 June, this time adding that enemy passenger liners should also be spared. Admirals Gustav Bachmann, Chief of the Admiralty Staff, and Alfred von Tirpitz, State Secretary of the Imperial Naval Office, both thought that by doing so Germany was admitting that the sinking of the Lusitania had been illegal and was giving up its best weapon against the UK.[33]

Unrestricted U-boat warfare did bring the USA into the war, but not for nearly two years. From a US point of view, the crucial difference between the British blockade and German unrestricted submarine warfare was that the British only interfered with US trade and property, whilst the Germans additionally killed Americans. The German problem in 1915 was that they did not enough U-boats to win the war by submarine warfare, but trying to do so would damage their relations with the USA.

This website contains a great deal of information about Lusitania and her passengers and crew.

[1] D. Preston, Wilful Murder: The Sinking of the Lusitania, Special Centenary edition. ed. (London: Doubleday, 2015 edition, first published 2002), p. xii; C. Simpson, Lusitania (London: Longman, 1972). Frontispiece.

[2] Naval Staff Monograph (Historical) 1925 vol. xiii, Home Waters part iv, February 1915 to July 1915. p. 169.

[3] Preston, Wilful, pp. 152-53.

[4] Ibid., pp. 162-67.

[5] Naval Staff vol. Xiii. pp. 169-72.

[6] A. S. Hurd, The Merchant Navy, 3 vols. (London: HMSO, 1921). vol. i, pp. 411, 413.

[7] R. K. Massie, Castles of Steel: Britain, Germany, and the Winning of the Great War at Sea (London: Jonathan Cape, 2004), p. 531.

[8] Naval Staff vol. Xiii. p. 172.

[9] R. Gray, Conway’s All the World’s Fighting Ships, 1906-1921 (London: Conway Maritime Press, 1985), p. 176.

[10] Preston, Wilful, p. 299.

[11] Ibid., pp. 131-2, 208.

[12] Simpson, Lusitania, p. 165.

[13] Hurd, Merchant. vol. i, pp. 420-24.

[14] Preston, Wilful, p. 394.

[15] Hurd, Merchant. vol. i, p. 414.

[16] Naval Staff vol. Xiii. pp. 171-2. pp. 171-72 and footnote 1 on p. 172.

[17] Simpson, Lusitania, p. 147.

[18] Preston, Wilful, pp. 423-25.

[19] Hurd, Merchant. vol. i, p. 418

[20] Simpson, Lusitania, p. 151.

[21] Preston, Wilful, pp. 436-44.

[22] Ibid., p. 444.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid., p. 432.

[25] Simpson, Lusitania, pp. 20-32.

[26] Preston, Wilful, pp. 391-92.

[27] Ibid., p. 108.

[28] Ibid., pp. 393-94.

[29] Ibid., p. 401.

[30] Ibid., pp. 402-3.

[31] Ibid., pp. 389-90.

[32] Quoted in Massie, Castles, p. 537.

[33] Ibid., pp. 539-40.