Major-General Charles Townshend’s 6th (Poona) Division, comprised of British and Indian troops, captured Kut-al-Amara on 28 September 1915. Townshend was then ordered to press on to Baghdad. He argued that he needed two divisions to do so but obeyed his orders when his protests were overruled.[1]

The British command structure was confused because of the way in which the British ruled India. Townshend’s immediate superior, General Sir John Nixon, answered to the Indian government, comprised of British officials, in Delhi rather than to the War Office in London. Austen Chamberlain, the London based Secretary of State for India, was concerned about the lengthening lines of communication and lack of river transport in a region with poor roads and no railways. Townshend wrote in his diary that Nixon ‘does not seem to realise the weakness and danger of his lines of communication…the consequences of a retreat are not to be imagined.’[2]

Nixon, however, claimed that marching the troops with land transport and lightening the river boats would avoid any ‘navigation difficulties.’[3] His view was accepted and the advance continued.

On 22 November Townshend’s troops encountered the Ottomans at the ruined ancient city of Ctesiphon, 22 miles from Baghdad. He believed that the enemy had 11,000 men and 40 guns but they actually had 18,000 men and 52 guns.[4] He had 13,756 men, 30 guns and 46 machine guns, not counting those on the gunboats Firefly and Comet, the armed launches Shaitan and Sumana or the four 4.7 inch guns on horse boats towed by the armed stern wheelers Sushan and Messoudieh.[5]

Townshend was forced to break off the action on 24 November. The next day his force started to retreat towards Kut, which was reached on 3 December. The lack of transport meant that the wounded, who continued to Basra suffered greatly, first travelling on unsprung 2 wheeled ox carts and then on over-crowded boats with inadequate medical facilities.[6] A. J. Barker argues in his authoritative history of the Mesopotamian Campaign that Nixon was not ‘entirely blameless’ but the [British] Indian government must be regarded as primarily responsible’ for the dreadful medical facilities.[7]

British casualties at Ctesiphon, the retreat and a further action at Umm-at-Tubal totalled 4,970: 711 killed, 3,890 wounded and 369 missing. A Turkish account says that the Ottomans lost over 9,500 men including deserters at Ctesiphon, with another giving their casualties excluding deserters as being 6,188. Their casualties at Umm-at-Tubal were 748.[8]

The British also lost the new gunboat Firefly, which was disabled when a shell hit her boiler and the old gunboat Comet, which ran aground when trying to help her. Sumana managed to rescue their crews with Ottoman soldiers already boarding the two stranded gunboats.[9]

Townshend reported initially that his division could hold out in Kut for two months, which was ‘a somewhat conservative estimate.’[10] By seizing local food supplies, putting his men on short rations and killing his animals for meat Townshend was ultimately able to hold out for nearly five months. His initial estimate forced the relief force to move before it was ready. It is strange that an officer who had made his name in a siege, that of Chitral on the North West Frontier of India in 1895, should make such a mistake.

By 24 April the situation in Kut was so desperate that a highly risky resupply mission had to be mounted. The river steamer Julnar was stripped of all unnecessary woodwork and armoured with protective plating. Manned by an all volunteer crew of Lieutenant Humphrey Firman RN, Lieutenant-Commander Charles Cowley RNVR, Engineer Sub-Lieutenant W. L. Reed RNR and 12 ratings she was to carry 270 tons of supplies to Kut.[11]

Cowley had a great knowledge of the River Tigris, having been employed by the Euphrates and Tigris Navigation Company. He had been born in Baghdad, was regarded by the Ottomans as being an Ottoman subject, so was likely to be executed if captured.[12] He had been born in Baghdad. He acted as pilot, with Firman captaining the Julnar.

She set off at 8 pm on 24 April, a dark, overcast and moonless night. Heavy artillery and machine gun fire tried to drown out the sound of her engines, but the Ottomans knew that she was coming. She soon came under rifle fire and could make no more than six knots because of a strong current. Ten miles from Kut she came under artillery fire. Two miles later a shell hit her, killing Firman and wounding Cowley, who took command. A few minutes later she struck a cable and drifted onto the right bank of the river. She was stuck, giving Cowley no choice but to surrender.[13]

Cowley was quickly separated from the rest of the crew. The Ottomans claimed first that he was found dead when the Julnar surrendered, then that he was shot whilst trying to escape. It is most likely that he was executed. He was a British subject, but he was aware that the Ottomans would execute him if he was captured.[14]

Cowley and Firman were both awarded the Victoria Cross posthumously. The citation, from naval-history.net, states that:

Admiralty, 31st January, 1917.

The KING (is) pleased to approve of the posthumous grant of the Victoria Cross to the undermentioned officers in recognition of their conspicuous gallantry in an attempt to re-provision the force besieged in Kut-el-Amara.:

Lieutenant Humphry Osbaldeston Brooke Firman, R.N.

Lieutenant-Commander Charles Henry Cowley, R.N.V.R.

The General Officer Commanding, Indian Expeditionary Force “D,” reported on this attempt in the following words:

“At 8 p.m. on April 24th, 1916, with a crew from the Royal Navy under Lieutenant Firman, R.N., assisted by Lieutenant-Commander Cowley, R.N.V.R., the ‘Julnar,’ carrying 270 tons of supplies, left Falahiyah in an attempt to reach Kut.

Her departure was covered by all Artillery and machine gun fire that could be brought to bear, in the hope of distracting the enemy’s attention. She was, however, discovered and shelled on her passage up the river. At 1 a.m. on the 25th General Townshend reported that she had not arrived, and that at midnight a burst of heavy firing had been heard at Magasis, some 8 1/2 miles from Kut by river, which had suddenly ceased. There could be but little doubt that the enterprise had failed, and the next day the Air Service reported the ‘ Julnar ‘ in the hands of the Turks at Magasis.

“The leaders of this brave attempt, Lieutenant H. O. B. Firman, R.N., and his assistant – Lieutenant-Commander C. H. Cowley, R.N.V.R. – the latter of whom throughout the campaign in Mesopotamia performed magnificent service in command of the ‘Mejidieh’ – have been reported by the Turks to have been killed; the remainder of the gallant crew, including five wounded, are prisoners of war.

“Knowing well the chances against them, all the gallant officers and men who manned the ‘ Julnar’ for the occasion were volunteers. I trust that.the services in this connection of Lieutenant H. O. B. Firman, R.N., and Lieutenant-Commander C. H. Cowley, R.N.V.R., his assistant, both of whom were unfortunately killed, may be recognised by the posthumous grant of some suitable honour.”

The British Official History of Naval Operations states that all ‘the crew were decorated.[15] The awards of the Distinguished Service Order and the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal to other members of the crew were announced on 11 November 1919.

Honours for Miscellaneous Services.

To be a Companion of the Distinguished Service Order.

Eng. Sub-Lieut. William. Louis Reed, R.N.R. For gallant and distinguished services as a volunteer in H.M.S. “Julnar” on the 24th April, 1916, when that vessel attempted to reach Kut-El-Amarah with stores for the besieged garrison.

To receive the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal.

E.R.A., 2nd Cl., Alexander Murphy, R.N.V.R., O.N. (Mersey) Z3/182. For most conspicuous gallantry as a volunteer in H.M.S. “Julnar” on the 24th April, 1916, when that vessel attempted to reach Kut-El-Amarah with stores for the besieged garrison.

P.O., 1st Cl., William Rowbottom, O.N. J2953 (Ch.). For most conspicuous gallantry as a volunteer in H.M.S. “Julnar” on the 24th April, 1916, when that vessel attempted to reach Kut-El-Amarah with stores for the besieged garrison.

The award of the Distinguished Service Medal to a group of ten ratings, listed on Naval-History.net, was announced the same day. It is likely that they were the other members of the crew, but the citations for the award of the DSM are not available.

Honours for Miscellaneous Services.

To receive the Distinguished Service Medal.

A.B. Herbert Blanchard, O.N. J13427 (Po.).

A.B. William Bond, O.N. J8490 (Dev.).

Ldg. Sto. Herbert Cooke, O.N. K6470 (Ch.).

Sea. John Featherbe, R.N.R., O.N. 6973A.

Sto., Ist.Cl., George William Forshaw, O.N. K18513 (Dev.).

Sto., 1st Cl., Samuel Fox, O.N. S.S.110714 (Po.).

A.B. Harry Ledger, O.N. J9539 (Dev.).

Sto., 1st Cl., Charles Thirkill, O.N. S.S. 115464 (Dev.).

A.B. Alfred Loveridge Veale, O.N. 215734 (R.F.R. Dev./B5936).

A.B. Montagu Williams, O.N. J44546 (Ch.).

The failure of Julnar’s mission meant that the only supplies available to the garrison of Kut were the tiny amounts that could be dropped by the small number of low performance aircraft available. Attempts were made to negotiate an end to the siege, but the Ottomans were not interested in British offers of gold or guns or prisoner exchanges in return for allowing the garrison of Kut to return to India or the fact that they would have to care for a large number of sick prisoners if the garrison surrendered. Townshend therefore surrendered Kut on 29 April.[16]

The Ottomans treated Townshend very well, his officers reasonably and his men very badly in captivity. During the siege 1,025 men were killed, 721 died of disease, 2,446 were wounded and 72 went missing. 247 civilians were killed and 663 wounded. Nearly 12,000 men went into captivity, of whom over 4,000 died. Their treatment eventually improved after representations from the US and Dutch Ambassadors.[17] Townshend’s reputation never recovered from his failure to inquire into the fate of his men whilst he lived in luxury in Istanbul. His performance in the campaign until Ctesiphon had actually been good: see this post.

[1] A. J. Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914-1918: Britain’s Mesopotamian Campaign (New York, NY: Enigma, 2009), pp. 91-92.

[2] Quoted in Ibid., p. 89.

[3] Quoted in Ibid.

[4] Ibid., pp. 97-98.

[5] J. S. Corbett, H. Newbolt, Naval Operations, 5 vols. (London: HMSO, 1938). vol. iii, p. 227; F. J. Moberly, The Campaign in Mesopotamia, 1914-1918, 4 vols. (London: HMSO, 1923). vol. ii, p. 71.

[6] See D. Gunn, Sailor in the Desert: The Adventures of Phillip Gunn, Dsm, Rn in the Mesopotamia Campaign, 1915 (Barnsley: Pen & Sword Maritime, 2013). for the experiences of a Royal Navy seaman in Mesopotamia. Chapter 48 describes the battle and Chapters 49-60 his evacuation after being wounded.

[7] Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914-1918: Britain’s Mesopotamian Campaign, p. 106.

[8] Corbett, Newbolt, Naval. vol. iii, p. 229.

[9] Ibid. vol. iii, pp. 228-29.

[10] Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914-1918: Britain’s Mesopotamian Campaign, p. 228.

[11] Corbett, Newbolt, Naval. vol. iv, p. 90.

[12] Barker, The First Iraq War, 1914-1918: Britain’s Mesopotamian Campaign, p. 212.

[13] Corbett, Newbolt, Naval. vol. iv, pp. 90-91.

[14] Moberly, Mesopotamia. vol. ii, p. 435, footnote.

[15] Corbett, Newbolt, Naval. vol. iv, p. 91, footnote 1.

[16] Moberly, Mesopotamia. vol. ii, pp. 452-57.

[17] Ibid. vol. ii, pp. 459-466.

Glasgow University's Great War Project

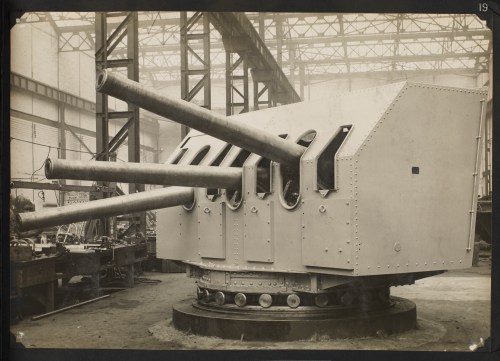

Naval guns produced by William Beardmore’s Parkhead Forge, University of Glasgow reference UGD100/1/11/3

Naval guns produced by William Beardmore’s Parkhead Forge, University of Glasgow reference UGD100/1/11/3